By Shaharaj Ahmed (’23).

An abridged version of this piece is slated to be published in the Singapore Policy Journal.

Public consensus that Singapore’s low-skill workers need to be paid more has sparked calls for more progressive and robust labour laws, including wage interventions such as the minimum wage. The government has acceded, in some way, through their own solution to the issue of stagnating low wages with the Progressive Wage Model (PWM). The PWM has been touted by some top government officials as “Minimum Wage Plus” [1] because on top of stipulating a basic wage, it also provides a clear structure for Singapore’s lowest workers to raise their wages by taking courses and more responsibilities in order to qualify for higher level positions and other promotions.

In theory, the policy seems ideal. However, in practice, it has limitations which many talk about but few truly understand. In this piece, I will be explaining the limitations of the PWM, particularly its effects on productivity and wages, legal ambiguity, and cost of implementation.

Productivity

As mentioned, the PWM codifies into policy the practice of increased productivity for increased pay. For example, if you are a cleaner and take a course to become a specialised waste disposal cleaner, then you get paid a higher wage. The PWM is currently being implemented in the landscaping, cleaning, and security industries. However, realistically, this notion of career development and increased productivity for low-skilled jobs in these industries is impossible to achieve for two reasons: a lack of room for increased efficiency and a lack of promotion opportunities.

The most basic reason as to why a worker may not be able to increase their productivity is that there simply is no more room for efficiency. In many of the jobs where the PWM is applicable — security, cleaning, and landscaping — if a worker is operating at their full capacity, then chances are that is the full productive capacity of any worker. This argument becomes clearer once we realise that there is nothing inherent about these jobs that require skills, significant training, or education. Whereas to be a doctor or a soccer player, one needs innate skill and/or many years of training, to be a cleaner is to merely clean. If a dishwasher can only wash 40 dishes an hour with current technology, then there is no way for the PWM to raise that rate to increase the dishwasher’s productivity. The only way to increase the productivity of that worker is to increase the technological capabilities of that worker. In a video interview, Mr. Raj Joshua Thomas, Nominated Member of Parliament and President of the Security Association Singapore, argued that employers, at least in the security industry, should invest in technology to expand the job scope of security guards [2]. Thus, while proponents may laud the PWM for stipulating a recommended wage band that employees can use to negotiate for higher wages, there is little demonstrable productivity increases that employees can offer to justify wage increases unless the industry itself invests in better technology and allows workers to use said technology after training.

The other main method through which the PWM promotes productivity is career promotion. This is an unlikely prospect in the industries the PWM is currently implemented in — security, landscaping, and cleaning. In these industries, senior positions — scarce to begin with — are always filled up. Many security guards, despite taking the time to undertake courses and training certifications to qualify for senior positions, often fail to get promoted because there is no space on the upper rung [3]. At the end of the day, with a pyramid hierarchy, most workers will have to do general, mundane work and only some will be selected for specialist work such as lift maintenance in the landscaping industry or managerial positions such as a senior security supervisor in the security industry. This seems to be a critical flaw of the PWM: to assume that specialist roles will continue to be produced, thus allowing junior workers to abdicate their generalist roles, without rewarding the workers who continue to shoulder the base responsibilities of the organisation.

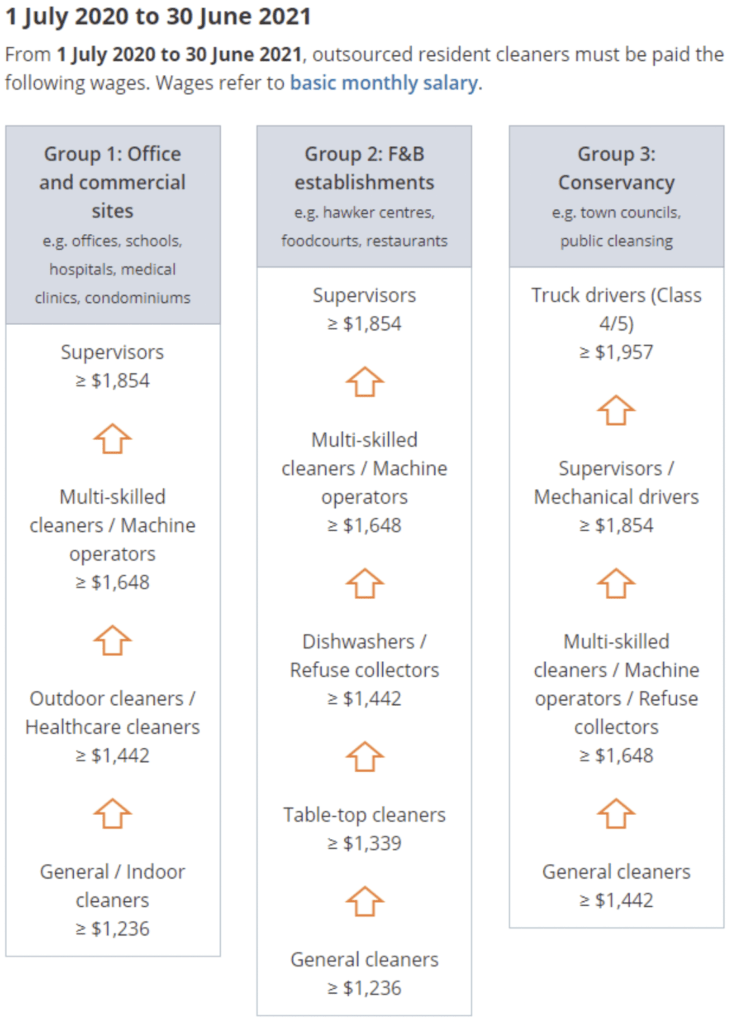

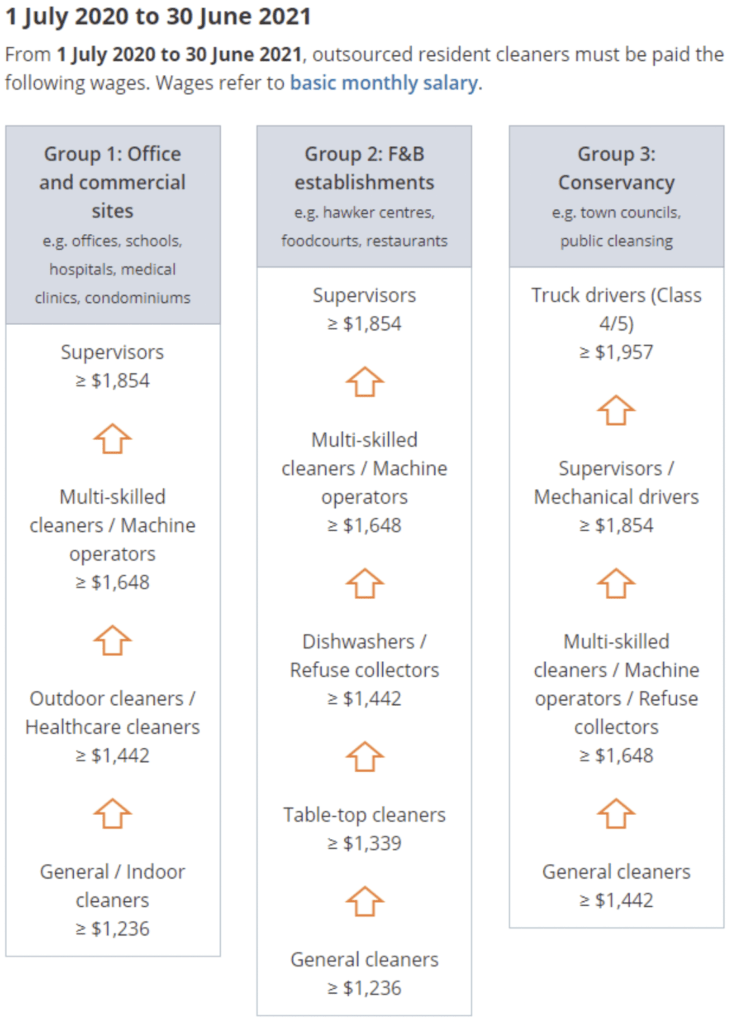

For example, let us observe the career ladder for a cleaner in the Group 3 cluster of the cleaning industry, as illustrated in Figure 1 below. A cleaner starts out with a base pay of S$1,442. While it is desirable from the cleaner’s perspective to take courses to become a supervisor and gain a base pay of S$1,854, it is also in their colleagues’ interests to take these same courses to qualify as a supervisor. Hence, there is collective upward pressure for an already scarce job. Thus, while there is a worker who does get promoted to the managerial position (assuming it is open) and gains a higher salary, the PWM does nothing for the worker who is forced to remain in the bottom rungs of the ladder despite being qualified to be promoted, because at the end of the day, someone has to do the general cleaning. Let us, however, assume a case where it is possible for everyone to be a supervisor and gain higher pay. Who then will do the general cleaning? It is this inflexibility of the PWM to recognise that most workers will not be able to climb the PWM ladder because of the lack of vacant senior positions that makes the promise of increased productivity a myth. This is evidenced by the fact that most PWM industries, particularly the security industry, are suffering from manpower crunches in junior positions, not senior ones. Everyone wants to be a manager.

Figure 1: Career ladders for the cleaning industry [4].

This flaw indicates the presence of a more problematic ideology pervading our conversations around income inequality: that workers are ‘worthy’ of more pay if they are higher up on the career ladder, and conversely, not ‘worthy’ if they are lower on the career ladder. For those at the bottom, this can mean an income that does not meet their basic needs, even as they are employed and work as best as they can. In addition, it implies that the essential base of general workers are less deserving, even though these workers are responsible for the bulk of daily operations.

Furthermore, in real life, the PWM theory of raising productivity falls into more issues. While in the discussion above we maintain the assumption that getting promoted means the worker receives differentiated and advanced work, employers may not have that type of work. Mr. Thomas noted in an interview with Rice Media that for the security industry, “[t]here is very little difference between a Level 1 officers’ job scope and a Level 2 officer, and even between Level 2 officers and Level 3 supervisor.” Career development is theoretical, at this stage, for most PWM workers [5].

Wages

The PWM also does not effectively raise wages for low-wage Singaporean workers, on six counts:

- it does not sufficiently encourage the promotion of elderly Singaporean workers;

- it does not take into consideration the mass inflow of foreign labour;

- the stipulated basic wage becomes a stagnant wage floor due to market oversaturation and a lack of business interest in raising wages;

- it does not ensure stability of the increased wages when companies change;

- its expansion into new industries reduces gross wages; and

- it does not provide a livable wage.

Firstly, the claim that PWM helps raise the productivities and incomes of low-wage Singaporean workers is nullified by the employment practices of firms and the demographics of the low-wage labourers. Many Singaporean residents in the PWM industries tend to be older and hence less able and slower. Consequently, firms prefer to hire foreign workers at the higher rungs of the PWM ladder [6], leaving elderly Singaporean workers at the lower rungs of the PWM ladder. Professor of Economics at University of Michigan, Prof. Linda Lim, corroborates this through her research, which found that employers tend to hire more able, younger foreign workers to fill up the upper roles, rather than older local residents, since they are able to gain more economic value from their employees this way.

The second structural issue is the PWM’s inability to manage the mass inflow of foreign labour into PWM-covered labour-intensive industries, which Prof. Lim has credited as the main depressors of wage growth for low-skilled labour in Singapore [7]. Hiring agencies have relied on foreign labour due to many reasons, key amongst them is costs. Particularly for the PWM industries, which face an aging workforce and labour shortages due to the unattractiveness of the roles, hiring foreign workers is an easier solution than offering higher wages for older workers. Thus, the inability of the PWM to contend with foreign labour inflows prevents industry-wide wage growth, denying Singaporeans in such industries higher wages.

We should note that foreign hiring is not a problem in all industries. Mr. Thomas reminds us that this is not the practice in the security industry due to various regulations on hiring foreign workers.

The third limitation of the PWM is that ironically it becomes a sticky wage floor. A sticky wage floor is a situation in which workers are unable to gain higher wages beyond the legal minimum. This could occur for a variety of reasons. One direct cause of this sticky wage floor is the market saturation in these industries. As a consequence of excess supply, cleaning, landscaping, and security outsourcing companies usually outbid each other to offer the lowest contract price possible (which companies are inclined to accept). This means that workers in these job types are paid the lowest wages legally possible. Mr. Thomas shared that the trade association has received sufficiently alarming feedback on regulatory infractions made by some security agencies, which flout PWM rules to underbid competitors [8]. These regulatory infractions demonstrate that market saturation has evolved to the point that firms are willing to depress wages to survive, even to the point of breaking the law.

Consequently, even when demand for services such as cleaning, dishwashing, security, or landscaping increases, wages remain stagnant. Professor of Social Work at the National University of Singapore (NUS), Prof. Irene Ng, posits [9] that when demand rises, more firms enter already saturated industries and each bid to the lowest point possible, driving wages down despite a rise in demand. Mr. Thomas mentioned that roughly 95% of the roughly 250 security agencies in the industry are small, indicating small barriers to entry and exit for firms within the industry. As a solution, he and his team have proposed setting up higher barriers to entry into the industry, such as raising the initial paid-up capital. However, these are yet to be legislated or adapted into policy. Since the PWM does not regulate foreign labour inflows or industry-wide practices, it may be good to expand the scope of the PWM to tackle these issues if we hope to drive up the wages of low-income Singaporeans.

Another reason for the sticky wage floor is that there are no incentives for employers to pay workers any higher. The most vivid remark I came across on this topic was from Channel NewsAsia’s (CNA) interview with Mr. Steve Tan, who is the executive secretary of the Union for Security Employees. He disclosed to CNA that in his tripartite negotiations, he came across a buyer who said “[the] same (security) uncle before and after? Why should I pay you S$50 more?” [10]. While policy-wise, the PWM actually provides a wage bracket as a guide for firms to pay their workers for each level, practically, firms are incentivised to pay the bare minimum [11].

Upon reflecting on this last comment, it seems that there is a case where employers might be prepared to pay a higher wage — if workers take on more responsibility. However, as previously pointed out, there is realistically little room for workers to do so. Thus, the interaction between wage and productivity hampers upward mobility under the PWM regime.

Mr. Thomas, however, disagreed on this point, replying that security workers do in fact have leeway in negotiating higher wages. One negotiating tactic is to use the fact that Covid-19 has increased demand for security workers through government initiatives such as SafeEntry booths, which increases the manpower needed by security agencies. It is important to note that this induced demand is, however, temporary. Another more substantial negotiating tactic is to remind security agencies of the manpower crunch they are facing. As noted by Rice Media and later confirmed by Mr. Thomas, many junior positions in security agencies nation-wide are vacant. However, it can also be argued that despite facing labour shortages, employers in the security industry may choose to forego hiring workers rather than pay higher wages. Thus, while PWM-covered workers may have some flexibility in negotiating for higher wages, gains from negotiation are not likely to be too substantial.

Altogether, the presence of a wage floor indicates a more troubling issue: the presence of a culture that is obsessed with cost rather than welfare. The above example of an employer haggling over a wage increase of S$50 that would have clearly benefited the low-income worker more than it would have to themselves indicates an unhealthy obsession with capitalist accumulation. Furthermore, the fact that many security agencies often bid contracts with the lowest contract value indicates the presence of employers more concerned with maximising their dollars rather than paying fairer wages to the workers providing the service. While it is not problematic to want services that are as efficient and valuable as possible, it is problematic when in doing so one’s workers are not paid what is needed to survive (as demonstrated later in the piece).

Fourth, wage gains from the PWM are unstable as they are constantly under threat of being reset to the base salaries. Prof. Ng documents that whenever the hiring firm puts out a tender for another outsourcing firm for its cleaning, landscaping, or security needs, there is a high chance that the incumbent outsourcing firm will lose the tender and have to leave the current location. If the incumbent outsourcing firm loses the tender and is forced to move, its employees have two options: move with it or stay at their current location. Employees usually choose to stay due to a factor of reasons such as proximity from home. If they choose to stay, their wages become reset to base amounts [12]. This is due to the fact that in the PWM’s implementation any experience or skills gains made under the PWM are recognised and rewarded within the firm alone, and cannot be transferred. Though the theoretical practice should be that all firms in the industry recognise the experience of the worker holistically, the incoming outsourcing company ultimately aims to bid the lowest contract, and so, are unable to pay more to experienced employees due to a lack of funds. Thus, even if an employee were to work in the same industry for 8 years, any progress on the PWM ladder and gains in wages would be reset if the outsourcing company were to change.

Fifth, though expanding the PWM into other industries increases basic wages of workers, there is evidence that gross wages fall. Recently, the Singaporean government has discussed expanding the PWM into other industries such as food and retail services. In his undergraduate thesis, Mr. Kenneth Ler, a NUS graduate, found that though there was an increase in basic wages after PWM came into effect, they found a decrease in gross wages (e.g. overtime pay, allowance, bonus) [13]. One hypothesis for this, which I believe to be most likely given the employment culture, is that employers cut down these benefits in order to comply with the PWM regulations, while also maintaining competitive contracts. Another hypothesis which Mr. Ler proposed, and Mr. Thomas independently brought up, was how these bonuses were to be used in order to reward productivity in the true spirit of the PWM. However, it is not clear why current employees must face a reset in their allowances and bonuses if they’ve worked with an employer for many years before the PWM was implemented. Thus, it is likely that we are to witness this effect in the next few months if the PWM is expanded into other sectors.

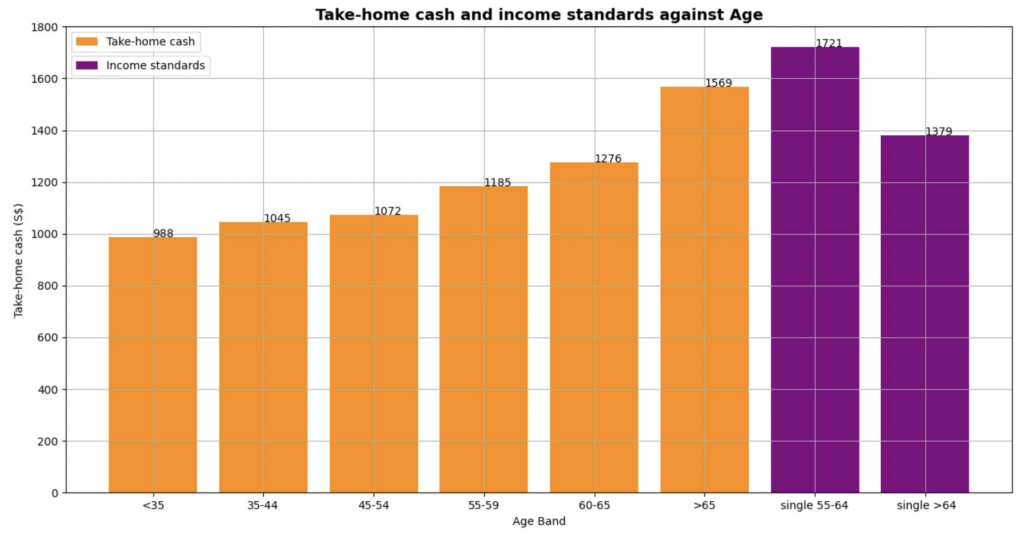

The final limitation of the PWM’s ability to raise wages is its inability to provide a liveable wage. A group of academics from the Nanyang Technological University (NTU), NUS, Duke-NUS, and Beyond Social Services conducted a study to ascertain the Minimum Income Standard (MIS) in Singapore, and found that for a household of a single individual aged between 55 and 64, the minimum income standards were S$1,721, assuming that the individual does not have any ‘chronic conditions and major illnesses’ [14].

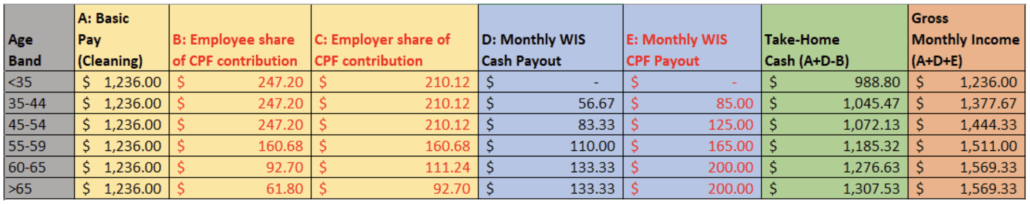

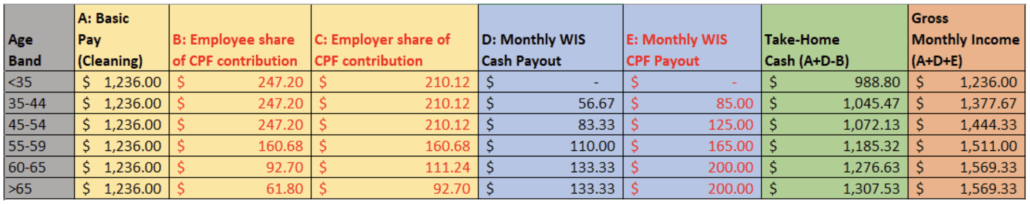

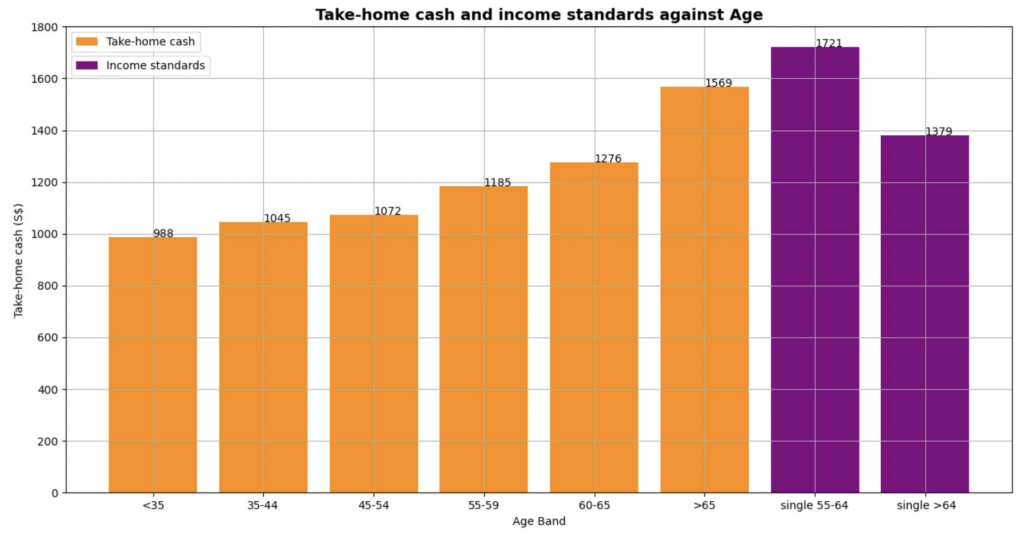

Mr. Lim Jingzhou, a community worker, calculated [15] how much PWM workers in different industries make, accounting for Workfare Income Supplement (WIS) payouts, a subsidy to boost the monthly wages of employees and self-employed workers who are paid below S$2,300. He found that for a worker in the cleaning industry within the age band of 55-59 takes home S$1,185.39, as shown in Figure 2. For this type of household, it is clear that the wages offered by the PWM, accompanied by WIS payouts, will not be sufficient to meet baseline income standards, as illustrated in Figure 3. However, the PWM does meet the basic income standards for single elderly households (elderly defined as those beyond the age of 64), as Mr. Lim finds that workers in the age band of those greater than 65 earn S$1,662, versus the baseline income requirements of this type of households at S$1,379. While single elderly households can technically support themselves with the PWM, it is morally undesirable to have elderly workers working in the first place, let alone working full time. Furthermore, let us not forget that their costs would definitely be higher (and the payouts from the PWM and WIS would be even more lacking) if they are facing medical bills or chronic/major illnesses — which is likely the case, as many elderly are forced into work at an old age to pay for medical bills for themselves or an elderly spouse or sibling.

Figure 2: Pay of workers in the cleaning industry for 1st July 2020 to 30th June 2021, accounting for WIS, CPF. [16].

There are two interesting notes within this discussion on wages. While the PWM’s proponents are proud that the scheme increases the pay of these workers, it is important to note the amount of money they receive versus the amount of money they are able to spend. The column labelled ‘Take-Home Cash’ represents the real wage cleaners are actually able to spend. This is because part of the money they are paid through the PWM goes to their Central Provident Fund (CPF), which they are unable to access until they are at least 55 years old (the age when a Singaporean resident can apply to withdraw money from their CPF account).

Figure 3: Data visualisation of take-home pay, accounting for WIS handouts and income requirements against age.

Another interesting note is the discrimination of age in subsidy handouts. As observed in figure 3 above, workers in the PWM industries gain higher take-home pay for the same position as they age due to the nature of the WIS policy (assuming they stay in the same position). This is problematic because in different stages of life, different workers have different needs to fulfill. For instance, younger workers such as those in their mid-30s may have dependent children for which many expenditures are realised. While this is a reflection of the government’s desire to move workers into higher-paying jobs, it does not take away from the fact that the low PWM floor means some needs of PWM workers are unmet.

It is important to note that the above discussion does not mean that every household is a single, elderly person or an individual between 55 and 64 years old. It is likely that many of the households are families with multiple dependents and single employed adults such as single, working mothers/fathers or old caregivers with elderly parents unable to work. While the MIS team is currently investigating what the minimum income benchmark is for other types of households, it is clear that with education, rent, medical fees, and much more, expenses for families can all pile up very quickly. More research needs to be done to account for households such as these, but it is clear that the PWM is unlikely to make the basic income standards required to live or support dependents [17].

Working Hours, Culture, and Complexity

There is a relationship between wages and working hours: more wages are paid for longer working hours. It is clear that PWM workers cannot make ends meet on their singular salaries alone. While there will be households with multiple workers or income streams, there will also be single households.

These households have two ways, other than borrowing money, to make up for the income shortfall: work overtime, and/or work multiple jobs. PWM workers often do both. For example, a Rice Media interview with security guards found even those who earn more due to being situated higher on the PWM ladder often take up additional jobs, even after factoring in overtime pay. The situation is likely worse for their lower-rung colleagues.

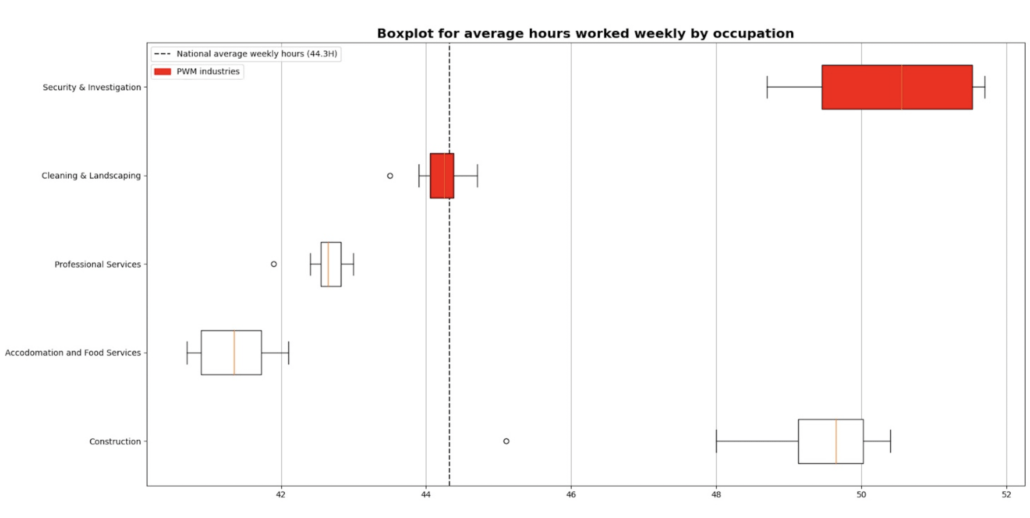

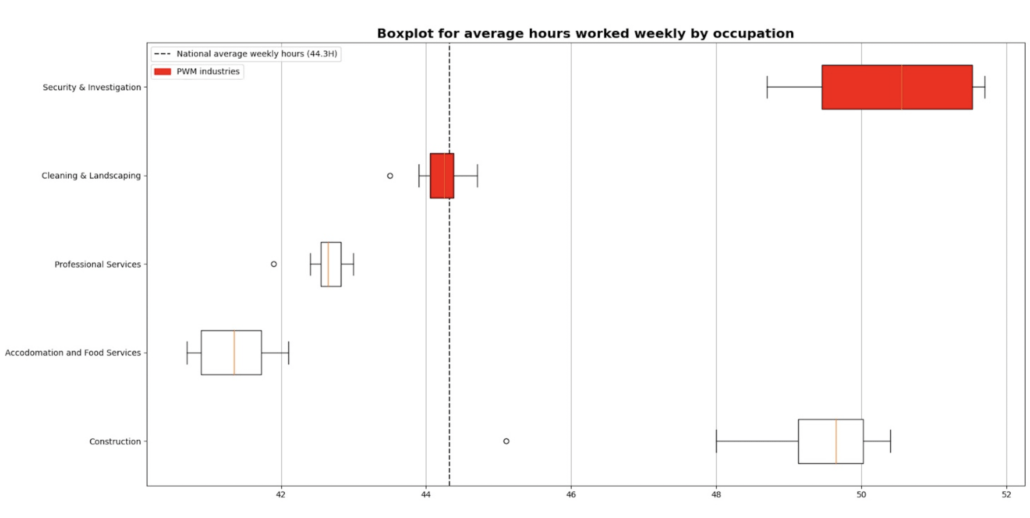

It is clear that employees in PWM industries are overworked. Workers in the security, cleaning, and landscaping industries work higher than average hours per week, as illustrated in Figure 4, and frequently work six-day work weeks. This is despite the fact that higher-paid white-collar workers in Singapore work the norm: 9AM to 5PM daily for five days a week.

Furthermore, many security guards often take on other jobs to supplement their income and support their families. A research study found that cleaners also take on longer hours to earn more money [18]. Unfortunately, the PWM’s provisions seem to give little consideration to working hours, despite its interaction with wages. It does seem to be that for the security industry, like the other two industries, the PWM has left its workers underpaid and overworked.

Figure 4: A comparison of average working hours of PWM industries against other professions [19].

While one could argue that cleaners and landscaping employees clock relatively lower working hours as compared to construction workers, it is important to note that cleaners and landscapers often work other part-time jobs to make ends meet. Hence, what is represented above may not necessarily represent the true duration full-time cleaners, landscapers, and security guards are working. What is salient, however, is the long working hours faced by PWM workers.

Collectively, while long working hours and insufficient pay have led to careers in the PWM industries being relatively unattractive to the younger Singaporean demographic, cultural perceptions are also a significant deterrent. In Singapore, it is seen as culturally and socially unfit to work in a menial job such as a cleaner, security guard, or landscaping role, when the norm is to work a traditional 9-5 desk job. The more significant deterrent is the fact that stipulated PWM wages are around 60-70% lower than the median wage. Though the PWM signals a commitment to increase wages, the cultural perceptions of the industry remain unchanged with the PWM.

The final limitation of the PWM is its complexity. One can understand the PWM as a wage system by which employees are given the opportunity to upgrade their skills and gain higher wages. However, it is also an entire policy ecosystem. It works in conjunction with WIS and Silver Support Scheme to top up wages of workers. Furthermore, the policy has to be coordinated with foreign dependency quotas. This is due to the fact that if employers are able to import labour at cheaper wages compared to Singaporean residents, then employers will do that rather than comply with PWM regulations. Finally, the government as, well as employers and labour unions, have to meet frequently to revise wages to account for inflationary pressures.

This complex nature of the PWM has three effects. Firstly, it makes it harder for employees under the PWM to fully understand what they are legally entitled to. Mr. Thomas had discussed how security agencies occasionally undercut each other [20]. While doing so, they often reduce the pay of employees below the PWM minimum, effectively breaking the law. Under the PWM, as there is complex bureaucracy involved, employees may not realise that they are being paid below the legal minimum or are having other benefits such as paid leave or breaks cut. This effect becomes exaggerated once we recognise that the people working these jobs tend to be less aware of the policy and legal codes that dictate their employment conditions and rights. The PWM is a broad policy network of wage floors, skills ladders, and subsidies which are vast amounts of information that low-income workers don’t have the time, resources, and confidence to understand. Prof. Ng finds in her research serious evidence of unaware cleaners and employers who take advantage of their unawareness to squeeze as much labour with minimum cost from them in this manner. Furthermore, considering the fact that low-income workers usually work overtime/other odd jobs to make ends meet, it is even more likely they do not have the time nor capacity to read up on such policies and legislation.

Secondly, the PWM is a challenge for the government to enforce as they must audit the books of firms to ensure that employers are complying with PWM regulations. Going back to the example of security agencies undercutting their competitors, a significant amount of manpower has to be dedicated by the government to ensure that security firms are not underpaying their employees as a means of gaining contracts. This second effect correlates with the third point that the bureaucracy maintaining the PWM overall becomes heavy and relatively expensive to maintain. Bureaucracy eventually becomes overladen in the sense that civil servants are required to go through a lot of training and paperwork to understand and enforce legislation that is complex, like the PWM.

In sum, while I believe that the PWM is a theoretically sound policy, as it stands and as it is being implemented at the moment, the PWM is insufficient in achieving the aim of providing a liveable wage for workers in the cleaning, security, and landscaping industries. It is a complex, expensive, and heavily bureaucratic system that falls short of providing a dignified existence for low-income workers. While I offer no alternative pathways towards providing a decent pay, the revisions that must come to the PWM or the PWM’s successor must take into account the demographic, cultural, and socio-economic conditions laid out in this piece.

Endnotes

- Tang, See Kit. “Tharman, PAP MPs Debate Minimum Wage, Policymaking with WP’s Jamus Lim.” Channel NewsAsia. September 3, 2020.

- Chew, Sophie, and Andre Frois. “What The PWM Could Do That A Minimum Wage Can’t: Make Buyers Pay Fair Prices.” Rice Media. Rice Media, November 7, 2020. https://www.ricemedia.co/current-affairs-features-progressive-wage-model-security-agencies/.

- Chew, Sophie, Edoardo Liotta, Louisa Lim, Andre Frois, and Ivan K. Wu. “How Much Progress Has The Progressive Wage Model Led To? We Asked Security Guards What They Think.” Rice Media. Rice Media, October 14, 2020. https://www.ricemedia.co/current-affairs-features-progressive-wage-model-security-guards/.

- “Progressive Wage Model for the Cleaning Sector.” Ministry of Manpower Singapore, 2021. Accessed July 25, 2021. https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/progressive-wage-model/cleaning-sector.

- Chew, Sophie, and Andre Frois. “What The PWM Could Do That A Minimum Wage Can’t: Make Buyers Pay Fair Prices.” Rice Media. Rice Media, November 7, 2020. https://www.ricemedia.co/current-affairs-features-progressive-wage-model-security-agencies/.

- This is true for at least the cleaning and landscaping industries; the security industry has to rely on the Singaporean labour pool and can at best hire Malaysians.

- Lim, Linda. “The Economic Case for a Minimum Wage: a Conversation with Linda Lim – Academia: SG.” Academia.edu. Academia.edu, July 25, 2020. https://www.academia.sg/academic-views/minimum-wage-conversation/.

- Chew, Sophie, and Andre Frois. “What The PWM Could Do That A Minimum Wage Can’t: Make Buyers Pay Fair Prices.” Rice Media. Rice Media, November 7, 2020. https://www.ricemedia.co/current-affairs-features-progressive-wage-model-security-agencies/.

- Ng, Irene YH, Yi Ying Ng, and Poh Choo Lee. “Singapore’s Restructuring of Low-Wage Work: Have Cleaning Job Conditions Improved?” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 29, no. 3 (2018): 308–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304618782558.

- Min, Chew Hui. “IN FOCUS: The Wage Debate – How to Lift the Salaries of Those Earning the Least?” Channel NewsAsia. Channel NewsAsia, February 3, 2021. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/in-focus-singapore-progressive-wage-model-minimum-wage-13229084.

- The most obvious way to test this claim will be to look at the data. However, I was not able to do so as at the time of writing, the data available for the Occupational Wage Survey is not granular enough. Only processed data and statistics (such as median, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile) are published. While I could have looked at the variation in the wages with the above statistics, this data is distorted as the PWM pays older workers more money due to WIS handouts, as covered in this piece.

- Ng, Irene YH, Yi Ying Ng, and Poh Choo Lee. “Singapore’s Restructuring of Low-Wage Work: Have Cleaning Job Conditions Improved?” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 29, no. 3 (2018): 308–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304618782558.

- Kenneth, Ler Yong Qin. “Has Singapore Raised the Wage Bar? Impact Evaluation of the Progressive Wage Model.” National University of Singapore. National University of Singapore, November 6, 2017. https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/139005.

- Ng, Kok Hoe, You Yenn Teo, Neo Yu Wei, Ad Maulod, and Yi Ting Ting. “What Older People Need in Singapore: a Household Budgets Study.” National University of Singapore. National University of Singapore, August 16, 2019. https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/157643.

- Lim, Jingzhou. “Research into PWM .” Facebook, October 25, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/lim.jingzhou.7/posts/10159297333509645.

- Based on figures derived from Mr. Lim’s calculations.

- An important caveat to note here is that security workers are however paid more than the figures calculated by Mr. Lim. This is why I have not included his calculations for security workers. The reason as to why this is so is because Mr. Thomas mentioned that by default security guards work 12 hours a shift for full-time positions. Thus, they earn about S$2,000.

- Ng, Irene YH, Yi Ying Ng, and Poh Choo Lee. “Singapore’s Restructuring of Low-Wage Work: Have Cleaning Job Conditions Improved?” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 29, no. 3 (2018): 308–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304618782558.

- I’ve included the working hours of these other occupations for a more representative comparison of PWM versus non-PWM industries. Furthermore, I’ve only analysed average working hours for the years 2019 and 2020 for relevancy and also because that is when the PWM came into effect for most of these industries. See Statistical Table: Hours Worked (mom.gov.sg).

- Chew, Sophie, and Andre Frois. “What The PWM Could Do That A Minimum Wage Can’t: Make Buyers Pay Fair Prices.” Rice Media. Rice Media, November 7, 2020. https://www.ricemedia.co/current-affairs-features-progressive-wage-model-security-agencies/.

Image credit: Unsplash

Professor Duan Jin-Chuan (right)

Professor Duan Jin-Chuan (right)