Is FinTech The Answer to Climate Change?

By Htet Myet Min Tun (’24) and Choo Wai Keat (’24).

Over the last two centuries, the human population has exploded nearly eight times over, to 7.9 billion in 2021. With this comes an acceleration in the level of environmental degradation, as nature fights a losing battle against the ever-growing demands of people on the planet. In an attempt to fulfill growing demands, technological advances — such as agritech, commercial agriculture, and fishing — have even emerged as the main catalysts and culprits of the level of deterioration we have witnessed and continue to witness today.

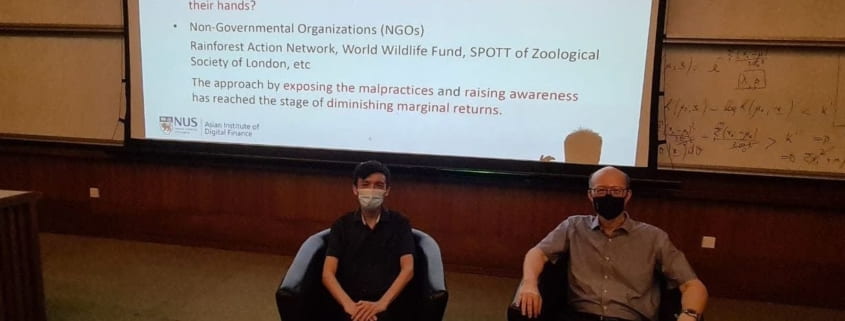

In a talk titled FinTech For A Greener World hosted by Roosevelt Network Yale-NUS College Chapter, Professor Duan Jin-Chuan (shown on the left), Executive Director at Asian Institute of Digital Finance and Jardine Cycle & Carriage Professor at National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School, proposed that technology does not always need to be a part of the problem, but rather a solution to cure the deteriorating environment. In fact, the Bottom-up Greenness (BuG) approach based on financial technology will be the most forward-looking solution to environmental degradation.

The Need for a Supply-Side Strategy

Currently, most approaches to address environmental degradation aim to alter consumption demand. Many current measures, such as the rise of conscious consumerism, tend to be based on arousing a sense of guilt and shame, as well as generally raising awareness of alternatives. Yet, these tactics may not be sufficiently powerful and long-lasting to fundamentally change the course of environmental conservation. This is particularly so in developing countries, where price sensitivity remains the most poignant factor in people’s minds as they opt for cheaper solutions which can guarantee survivability, regardless of the impact they exact on the environment.

At the root of these problems are misaligned economic incentives. When push comes to shove, many consumers opt for low-cost, environmentally damaging solutions because the environmental toll of using these products is largely invisible. To effectively discourage people from adopting environmentally unsustainable actions in their production and consumption requires an approach which forces individuals to internalise the full environmental costs of their actions.

On the other hand, a supply-side strategy is characterised by changing how goods and services are produced and delivered, curbing production before it can even begin to morph into a demand-side problem.

Some existing policies do employ this approach — for instance, Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) rating agencies penalise companies if their environmental record is less than ideal, while environmental non-governmental organisations (NGO) seek to expose companies’ malpractices and raise awareness of environmental issues.

These measures force companies to bear some of the negative externalities resulting from their actions. However, Prof. Duan argues that both are not flawless, as the former relies on commercial entities which may have alternative motivations, whereas the latter has now reached a plateau and is reaping increasingly diminishing marginal returns.

Enter the Bottom-up Greenness (BuG) Approach

The (BuG) approach could address the issue of economic incentives and apply a supply-side strategy to promote environmental sustainability. This strategy rests on two key pillars — technology and economic incentives. For the former, the application of digital technology and use of modern analytics can establish an evidence-based greenness measurement infrastructure and enable prediction and aggregation in supply chains. For the latter, financial institutions such as banks would consider the aforementioned evidence-based greenness metrics and grant greener companies concessional loans. A bank’s regulatory compliance would rest on whether its portfolio has satisfied greenness standards, and hence, banks would be encouraged to offer more concessional loans to greener entities. In such a model, all players are economically incentivised to strive towards environmental sustainability.

Prof. Duan highlights that a pilot using the BuG model is slated to be launched by the Asian Institute of Digital Finance in Indonesia’s palm oil industry.

In this model, Using the Internet of Things (IoT), data on palm oil smallholders’ key environmental behaviours, such as their green practices and the level of environmental pollution they cause, can be collected, using satellite images and IoT devices. The research team plans to work with a NGO to establish standards for determining greenness scores and equip university students with skills to assign these scores to smallholders on the ground. Subsequently, research institutes will develop a supervised machine learning model, which scales up the IoT system to more palm oil smallholders, and with a larger sample, generate predicted greenness scores. The greenness scores of these smallholders affect that of other nodes in the palm oil supply chain, i.e. the greenness score for a node in the supply chain — for instance, a palm oil mill or a palm oil company — is partially determined by the greenness scores of the suppliers it sources from.

This illustrates BuG’s unique ecosystem-level approach. Since greenness scores are assigned not at palm oil companies themselves but tied to every node of the palm oil companies’ supply chain, should compel companies to take ownership at every step of the way.

At the same time, the BuG approach also accrues several benefits. Firstly, the provision of concessional loans to smallholders would increase financial inclusion, as these entities can more easily gain access to capital. Secondly, the assignment of greenness scores is now bottom-up and more accurate, as opposed to a top-down process rooted in third-party observations. Thirdly, audits can be easily conducted to maintain system integrity, and feedback can be smoothly provided to improve existing procedures. Crucially, auditors can also help to champion environmental sustainability to the population at large, as they are equipped with the knowledge and expertise in this domain.

This then creates a win-win system for all stakeholders, where greenness is integrated into every step of the supply chain.

Potential Roadblocks

BuG provides an innovative alternative to the current ESG ecosystem. However, we acknowledge that there may remain some practical limitations which could hinder the maximum realisation of its potential.

Firstly, BuG may be difficult to implement on the ground, as the incentives of different stakeholders may not align to the extent that they are willing to cooperate on such a project. This might result in an unwillingness to adopt the BuG framework because the environmental objective of every institution differs. For example, NGO-set standards might be higher than what companies are willing to achieve.

Next, the feasibility of this policy may be up for contention. The BuG is mainly targeted at entities in developing countries. However, these countries may lack sufficient infrastructure and administrative capacity to manage stringent tracking and oversight requirements. This is compounded by the fact that a significant proportion of financial transactions in developing countries occur via informal means.

Lastly, even upon project launch, the BuG mechanism will be primarily run by financial institutions. This could lead to the recurrence of malpractice that currently plagues ESG systems, such as the possibility of established companies “gaming the system” to achieve high ratings on paper. Thus, for the BuG approach to realise its full potential, greater government oversight might be needed in structuring these collaborations.

Can Bottom-Up Greenness be the answer?

In conclusion, BuG is an approach that can be highly effective under certain conditions: stakeholder incentives must align; the environmental issue at hand must be easily resolvable without the presence of entrenched interest groups who stand to gain from the status quo; and efficient institutions must execute the policy.

We acknowledge that this may not always be possible due to the different circumstances of every industry and country. As such, the BuG approach can serve as a useful complement to other less market-friendly approaches, such as demand-side strategies based on nudging perception or governmental legislation.

As the world approaches a critical juncture in our fight against climate change, it is now more urgent than ever to conduct a thorough review of existing processes and leverage on the strengths of different players to fashion solutions and foster a more environmentally friendly economy and society. The emerging FinTech industry has great potential to do so. It is our hope that this potential can be translated into policy, action, and reality in the near future.

Professor Duan Jin-Chuan (right) spoke to Yale-NUS College students in a dialogue session in April.

Professor Duan Jin-Chuan (right) spoke to Yale-NUS College students in a dialogue session in April.

The Roosevelt Network Yale-NUS College Chapter would like to convey its deepest appreciation to Prof. Duan for his insightful sharing.

The New Paper

The New Paper

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!