Budding Entrepreneurs from a Young Age

By Choo Wai Keat (’24), Dineshram Sukumar (’24), Htet Myet Min Tun (’24), Sean Low (’24), Thimali Bandara (’24), and Zen Alexander Goh (’23)

Young Singaporeans lack exposure to entrepreneurial activity, leading to a general sentiment that they are not equipped for the endeavours of entrepreneurship [1]. To counter this, the Ministry of Education (MOE) should set up a dedicated body overseeing entrepreneurship education at secondary and pre-tertiary levels to increase exposure to entrepreneurial activities.

Background and Analysis

The Global Innovation Index consistently names Singapore as one of the top 10 strongest innovation sectors globally by government support and business ecosystem [2]. Yet, Singaporean youths still lag behind their ASEAN counterparts in entrepreneurial drive, highlighting Singapore’s overall lacklustre entrepreneurial landscape [3]. This could be traced back to the fact that Singaporean youths lack exposure to entrepreneurship in the mainstream education system, which mainly prepares students for the labour market. In the current education system, students are either (1) closed off to entrepreneurship as a viable career, or (2) unconfident of their skills in starting a business, even if they have the interest. These shortcomings carry socio-economic consequences—from prospective entrepreneurs missing out on their dreams, to society potentially missing out on the next billion-dollar idea and the jobs tied to it.

To draw a distinction between actual entrepreneurship and other forms of self/informal employment (e.g. gig economy micro-entrepreneurship, direct selling, etc.), entrepreneurship is defined as “the activities of an individual or a group aimed at initiating economic activities in the formal sector under a legal form of business” [4]. Given the importance of the innovation sector, encouraging entrepreneurship has been a key policy thrust of the government. However, current initiatives of startup incubators, grants and enterprise programs do not target the root cause of the problem and hence have been insufficient in improving the entrepreneurial landscape. These programs are mostly focused on helping entrepreneurs at universities scale up their businesses while there are limited avenues for Singaporean youths to acquire startup skills, particularly at the pre-university level. This creates a knowledge gap where students interested in entrepreneurship cannot find avenues to progressively develop their skill set before being thrown into the deep end. Additionally, these programs are only impactful for a small group of participants; the wider mass of students remain unexposed to entrepreneurship. The flaws of the existing schemes, therefore, perpetuate the problem of entrepreneurship being an overly niche path open to only a select few.

With entrepreneurship recognised as an effective means for countries to nurture homegrown enterprise champions and create jobs, pedagogies for entrepreneurship education are at the forefront of discourse in many European educational institutes; these offer a playbook for Singapore to adapt from. There are three ways to teach entrepreneurship: Education for Entrepreneurship involves imparting concrete business skills to students with a focus on starting a business; Education about Entrepreneurship implies learning about entrepreneurship as a socio-economic phenomenon; Education through Entrepreneurship connotes developing soft business skills in students through project work [5]. Each of these pedagogies have different uses and some are already being implemented at the more progressive private schools in Singapore. However, students in mainstream public schools are still systematically excluded.

Therefore, encouraging entrepreneurship education in Singapore is not so much about reinventing pedagogies, but adapting established methodologies such that entrepreneurial education becomes accessible to all.

Talking Points

- A Central Body for Entrepreneurship Education: A central dedicated body is tasked to expose students to entrepreneurship through mentorship, experiential opportunities and activities early on, before they steer away from entrepreneurship indefinitely.

- Engaging Local Entrepreneurs Directly: Partnering Enterprise Singapore (ESG) and leveraging the resources of the National Youth Council (NYC) to run this program enables direct access to Singapore’s entrepreneurs in different sectors, facilitates immersive experiences for students within the entrepreneurship ecosystem, and streamlines the process of engaging entrepreneurs.

- A Student-Driven Entrepreneurship Community: Networking student members of individual school clubs at the zone level opens up opportunities for ground-up collaboration. This creates a conducive, encouraging and accessible community environment to spark ideas and network, closely mirroring the entrepreneurship community at large.

The Policy Idea

To provide entrepreneurship education to all students who are keen, Singapore’s MOE should partner with ESG [6] to establish an industry-backed, centrally managed entrepreneurship interest group. This group, the Organisation for Entrepreneurial Incubation (OEI), should be open to all secondary school students.

Governmental Organisation and Interest

ESG provides direct industry access and engages entrepreneurs to facilitate this program’s execution. Concerned with developing the start-up space in Singapore, ESG would hence be interested to groom potential entrepreneurs during their formative years.

Simultaneously, MOE itself desires to build ‘entrepreneurial dare’ [7] within students.

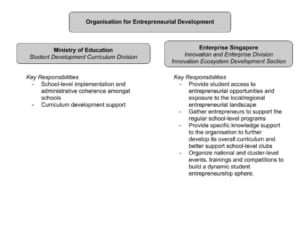

Between MOE and ESG, responsibilities concerning the initial implementation and longer-term operations of such a system-wide are tentatively divided as follows;

The National Youth Council (NYC) runs its own calendar of entrepreneurship-oriented programs, with a good fielding of panelists, advisors and partner businesses [8]. As NYC is an existing partner with MOE [9], it is an avenue from which to leverage resources for the broader school system. This widens the reach of NYC’s resources, resulting in greater, coordinated progress in entrepreneurship education.

Policy Analysis

Using a combined pedagogy of Education for Entrepreneurship and Education through Entrepreneurship will improve entrepreneurial attitudes by increasing students’ willingness and ability to pursue entrepreneurship as a career [10]. Technical skills workshops allow students to better grasp business concepts and prime them to take full advantage of the initiatives already offered at universities [11]. The project component of the curriculum consolidates learning in an engaging way and is instrumental in developing soft skills [12] that are equally important for entrepreneurial success. Together, the curriculum empowers students to believe they have what it takes to successfully start a business, addressing a root cause of lacklustre entrepreneurial drive in Singaporean youths [13].

Having this Entrepreneurship Club in secondary schools means nurturing students’ interest in entrepreneurship early on: important because students’ interest in entrepreneurship falls with each grade level, according to a US Gallup poll [14]. The non-highstake environment we propose allows for an atmosphere where failure is accepted and not harshly criticised. This mindset of being ‘open to risk and failure’ has been shown to be crucial to entrepreneurship [15] and important in life. The Entrepreneurship Club is efficient because the resources spent on it will only be used on those who are actually interested in entrepreneurship, and its flexibility means that participation in it will not hinder students’ academics or other passions.

To ensure accountability and equal and efficient spread of resources, the Entrepreneurship Club will function in each school as a chapter of a larger umbrella organisation. This central body will act as the bridge between various stakeholders, responsible for quality control and budget allocation across schools. Having this larger dedicated body—committed with specialised full-time staff to monitor individual Entrepreneurship Clubs—ensures they are run effectively for a long period of time. Notably, school-level clubs will be connected within their school clusters to expand entrepreneurial networks, facilitating cooperation and interaction and leveraging common resource pools. This further allows for collaboration across all schools in Singapore, thereby allowing students the experience of real-world collaboration, and also provides them with exposure to other youth and their ideas. This can act as a motivation for youth.

Having academic teachers teach entrepreneurship is one of the main shortcomings of entrepreneurship education case studies abroad. Our policy overcomes this by leveraging real-world entrepreneurs of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as mentors for the students. These mentors make entrepreneurship more intimate and relatable for aspiring students, making students more likely to view an entrepreneurial career more favourably. These entrepreneurs would carry out workshops on specific skills, or share about their entrepreneurial journey. Our policy recognises and leverages on the vested interests of these stakeholders (industry partners and entrepreneurs) in having a developed entrepreneurial scene. We are confident that the networking opportunities available when working with the government will be sufficient motivation for SME entrepreneurs, as shown by existing NYC partner members. Furthermore, participating entrepreneurs will have access to a pool of talented youth.

Key Facts

Studies indicate that the most important factor in determining whether one opts in to entrepreneurship is the individual’s perceived skills to succeed as an entrepreneur [16]. Yet, according to 2012 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) surveys, only 26.6% of surveyed Singaporean youths felt that they had the skills and technical expertise needed to start a business [17]. Likewise, Singapore ranked 23 out of 25 selected innovation-driven economies on an index meant to measure perceived entrepreneurial skills in graduates [18]. Therefore, it is fair to consider the lack of entrepreneurial skills training as a significant obstacle to entrepreneurial spirit in the Singaporean youth.

Endnotes

- “Youth Conversations Digital Sensing”. 2020. National Youth Council. https://www.nyc.gov.sg/en/initiatives/resources/youth-conversations/.

- “Singapore’s IP Ranking”. 2020. IPOS. https://www.ipos.gov.sg/who-we-are/singapore-ip-ranking.

- Seow, Joanna. 2019. “Poll: Singapore Youth Less Keen On Being Entrepreneurs Than Asean Peers”. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/business/poll-spore-youth-less-keen-on-being-entrepreneurs-than-asean-peers.

- Marcotte, Claude. 2013. “Measuring Entrepreneurship At The Country Level: A Review And Research Agenda”. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (3-4): 174-194. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.710264.

- Johansen, Vegard. 2012. “Entrepreneurship Education In Secondary Education And Training”. Scandinavian Journal Of Educational Research 57 (4): 357-368.

- Enterprise Singapore is a statutory board tasked with nurturing homegrown businesses, including startups.

- Ng, Chee Meng. 2017. “Wanted: Joy Of Learning, Entrepreneurial Dare In Students”. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/wanted-joy-of-learning-entrepreneurial-dare-in-students.

- NYC Members: https://www.nyc.gov.sg/en/about-us/#members

- NYC Partners: https://www.nyc.gov.sg/omw/partners

- Moberg, Kåre. 2014. “Two Approaches To Entrepreneurship Education: The Different Effects Of Education For And Through Entrepreneurship At The Lower Secondary Level”. The International Journal Of Management Education 12 (3): 512-528. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2014.05.002.

- Startup incubators, grants, networking opportunity, expertise

- Such as public speaking, communication, networking, project management

- Students lack confidence to start own business, even if they initially wanted to: cite GEINDEX

- Gallup, Inc. 2020. “Minority, Young Students More Entrepreneurially Inclined”. Gallup.Com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/166808/minority-young-students-entrepreneurially-inclined.aspx.

- “Why Should We Bring Entrepreneurship Education To Schools?”. 2020. Skillsforthefuture.Eu. http://skillsforthefuture.eu/get-inspired/580-why-should-we-bring-entrepreneurship-education-to-schools.html.

- Gomulya, David. 2015. “Entrepreneurship In Singapore: Growth And Challenges”. The Entrepreneurial Rise In Southeast Asia, 35-67.

- Gomulya, David. 2015. “Entrepreneurship In Singapore: Growth And Challenges”. The Entrepreneurial Rise In Southeast Asia, 35-67.

- Gomulya, David. 2015. “Entrepreneurship In Singapore: Growth And Challenges”. The Entrepreneurial Rise In Southeast Asia, 35-67.

Image Credit: Unsplash | Alesia Kazantceva

Nikkei Asia

Nikkei Asia

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!