WeCARE: Expanding childcare awareness to facilitate employment for single mothers

By Afiya Dikshit (’23) and Lim Tian Jiao (’23)

To help single mothers under 35 years old secure sustainable employment, Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA) and Government Technology Agency (GovTech) should develop a mobile application, WeCARE, to make childcare information more accessible. WeCARE should be publicised under ECDA’s existing KidSTART programme.

Background and Analysis

Many single mothers under 35 years old face severely reduced employment opportunities. In 2017, the average gross monthly income of working unwed mothers under 35 years is SGD 1,800, which is in the 15th percentile of gross monthly income in Singapore, while their median income is SGD 600, which is in the 1.5th percentile. Although these statistics only refer to unwed mothers, we believe a similar disparity in incomes exists for other single mothers because of difficulties in juggling work and caregiving responsibilities [1]. This clear disparity in income contributes to a lack of financial capabilities for single mothers.

Lack of childcare support is a major factor for this; caregiving responsibilities force “single parents…to work in part-time jobs that pay poorly” [2]. The inability to find childcare is a leading cause of unemployment and makes it difficult to maintain employment or attend job interviews. [3]

Single mothers do not take up childcare for various reasons. Firstly, many single parents see childcare as a service that they cannot afford [4]. Without sufficient incomes, they cannot afford to send their young children to childcare, yet without a safe space for their child, they are unable to find better employment. This leads to a Catch-22 situation, where single mothers cannot start working and raise their incomes unless their children are looked after, but they are unable to send children to childcare without sufficient incomes. [5]

However, this is a false paradox. ECDA’s Kindergarten Financial Aid Scheme (KiFAS) heavily subsidises early childhood education [6]. Households with a gross income of less than SGD 3,000 can pay just SGD 3 a month for full-day childcare at any of the 572 centres under the Anchor Operator Scheme [7], which receive government funding in return for capping their fees. As such, childcare fees are no longer prohibitive for the vast majority of lower-income families [8].

Rather, the lack of awareness of available schemes is a larger problem. “Time and again”, single mothers were found not to “know what further help might be available to them, or where to seek it” [9]. Lack of ready information about assistance schemes inhibits time-poor single mothers from comprehensively seeking out appropriate schemes and options.

Furthermore, the Housing Development Board’s policies do not consider single mothers with children as a family nucleus, so single mothers under the age of 35 are not eligible for subsidised housing. 75% of these mothers use rental or temporary housing [10], often with a maximum tenure of two years [11]. This makes it difficult for them to commit to enrolling children in childcare due to transportation and logistical uncertainty.

Such limitations make it especially difficult for single mothers to capitalise on existing schemes that alleviate the financial burden of childcare. This may trap mothers and children in a cycle of dependency and insufficient income.

Talking Points

- Single mothers lack access to sustainable and economically viable employment because of a perceived lack of suitable childcare, although government schemes already make childcare affordable for low-income single mothers.

- Single mothers face uncertainty about the logistical feasibility of childcare options for their children as they often have to shift living spaces and may be unaware of transportation facilities.

- Creating a mobile application that allows mothers to find suitable childcare centres in terms of cost, location and transportation helps mothers to coordinate more efficiently, while also showing them the convenience and ease at which they can operate.

- Disseminating information about the app through KidSTART, an existing door-to-door visitation programme for vulnerable families, can raise awareness about affordable childcare options.

The Policy Idea

We recommend that a mobile application, WeCARE, be created under GovTech. WeCARE will be designed to feature childcare centre locations, contact and transportation details and timings.

Our target group is unwed, widowed, or divorced mothers, under the age of 35, with children between 18 months and 6 years, and with gross monthly incomes lower than SGD 2,000. WeCARE will help these mothers find suitable childcare centre plans, providing them information about childcare timings and prices based on their location and income. This will make access to childcare centres easier.

We suggest using ECDA’s existing KidSTART Home Visitation programme to publicise WeCARE. When children turn 18 months old, Home Visitors will introduce WeCARE to mothers in the target group during their scheduled home visits.

Key WeCARE features are highlighted in the Appendix.

Policy Analysis

WeCARE provides single mothers with greater support to access long-term, formal childcare, so that they may seek and sustain employment. Given that Covid-19 has disproportionately affected lower-income earners in Singapore — where 51% experienced an income decline of more than 50% — an employment-oriented solution is timely [12].

The lack of secure housing for single mothers is a huge factor that hinders their utilisation of childcare facilities. With WeCARE, they can conveniently search and determine efficient and suitable plans and schemes for themselves and monitor the logistics of sending their children to a childcare centre.

Our smartphone-based solution is equitable as it does not require users to own laptops to easily navigate key functionalities. Given that 9% of residents who did not own a laptop cited cost as their main reason, a mobile application could be more accessible for low-income mothers [13]. A 2017 study found that the average American spends 90% of their mobile time in apps rather than the mobile web. As these figures are likely to be similar in Singapore, mothers will likely find an app more intuitive and convenient.

WeCARE is in line with the government’s Smart Nation digitisation drive, which aims to equip Singaporeans with technology to enhance everyday living [14]. For instance, Smart Nation initiatives have digitised hawker centres and introduced LifeSG, an integrated mobile application to access government services [15]. In addition, the government’s official Covid-19 contact tracing app, TraceTogether, has 2.4 million downloads, showing that WeCARE has the potential for widespread adoption [16].

Furthermore, the government can quickly gather childcare data from 822 private childcare operators through ECDA’s Partner/Anchor Operator Schemes [17]. ECDA-disseminated funding for the new school year could be made contingent upon them submitting relevant information for the app.

ECDA’s KidSTART Home Visitation scheme has home visitors regularly visit parents/guardians of eligible children from lower-income households to support them in child growth, health and nutrition till the child is three years old. The scheme has reached over 900 children since 2016, a number which is set to grow [18].

Leveraging on KidSTART allows us to directly introduce mothers to WeCARE and to subsidised childcare, addressing their lack of awareness about available options. Previous house visits by ECDA, pre-schools and voluntary welfare organisations (VWOs) have successfully increased preschool attendance among lower-income families [19].

Furthermore, using KidSTART as a publicity vehicle is feasible and cost-effective as home visitations already occur on a regular basis. Building upon this scheme requires minimal training and expertise for Home Visitors.

Key Facts

- The average monthly income of single unwed mothers under 35 in 2017 is SGD 1,800, while the median monthly income is SGD 600; the average and median income in Singapore is SGD 4,563 and SGD 4,232 respectively [20].

- Current subsidies mean that for households with a monthly income of less than SGD 3,000, full-day childcare costs just SGD 3 [21].

- Singapore’s TraceTogether app was downloaded by 2.4 million users and has 1.4 million active users, showing the potential attractiveness of app-based interventions [22].

Appendix

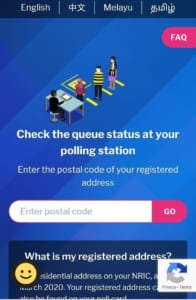

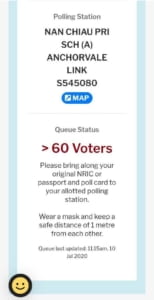

Fig. 1: Screen grabs from the Singapore Elections Department’s website. This website, https://voteq.gowhere.gov.sg/, allowed Singaporeans to quickly find out their polling station information simply by keying in their postal code. Similarly, WeCARE will present users with a list of childcare centres and their monthly rates when they key in their postal code and monthly income.

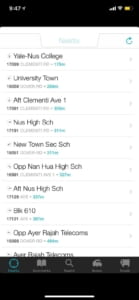

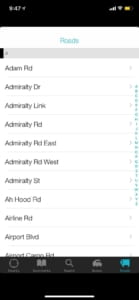

Fig. 2: Screen grabs from SG Buses, a popular app displaying bus timings. Using a similar format, WeCARE will list all school bus timings for each childcare centre, allowing single mothers to see their transport options at a glance.

Endnotes

- Thiagarajan, Palaniappan. “Work-Family Role Strain of Single Parents: The Effects of Role Conflict and Role Ambiguity.” Marketing Management 17 (January 2007): 82–94.

- Glendinning, Emma, Catherine Smith, and Md Kadir. “Single-Parent Families in Singapore: Understanding the Challenges of Finances, Housing and Time Poverty.” Lien Centre for Social Innovation: Research, 2015, 6.

- “Single Parents.” Single Parents | Research and Campaigns. Association of Women for Action and Research, March 1, 2017. https://www.aware.org.sg/research-advocacy/singleparents/.

- Tai, Janice, and Priscilla Goy. “Torn between Work and Childcare.” The Straits Times, January 19, 2016. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/torn-between-work-and-childcare.

- Glendinning, Emma, Catherine Smith, and Md Kadir. “Single-Parent Families in Singapore: Understanding the Challenges of Finances, Housing and Time Poverty.” Lien Centre for Social Innovation: Research, 2015.

- “Subsidies and Financial Assistance.” Early Childhood Development Agency. Accessed October 9, 2020. https://www.ecda.gov.sg/Pages/Subsidies-and-Financial-Assistance.aspx.

- Early Childhood Development Agency. “Annex C: Anchor Operator and Partner Operator Schemes.” Media Room. Ministry of Social and Family Development, 2020. https://www.msf.gov.sg/media-room/Documents/Annex%20C%20-%20Anchor%20Operator%20and%20Partner%20Operator%20Schemes.pdf.

- “The Big Read: Educators Flag Absentee Rate of Children of Low-Income Families as a Concern.” TODAYonline, August 1, 2015. https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/big-read-educators-flag-absentee-rate-children-low-income-families-concern.

- Glendinning, Emma, Catherine Smith, and Md Kadir. “Single-Parent Families in Singapore: Understanding the Challenges of Finances, Housing and Time Poverty.” Lien Centre for Social Innovation: Research, 2015, 1–34.

- Rep. Single Parents’ Access to Public Housing: Findings from AWARE’s Research Project. Association of Women for Action and Research, 2016.

- Glendinning, Emma, Catherine Smith, and Md Kadir. “Single-Parent Families in Singapore: Understanding the Challenges of Finances, Housing and Time Poverty.” Lien Centre for Social Innovation: Research, 2015, 1–34.

- DBS, “DBS on Covid-19’s Impact on Singapore Residents’ Financial Health: More Help Needed for Lower Income Group,” Live More, Bank Less | DBS Bank, last modified August 18, 2020, https://www.dbs.com/newsroom/DBS_on_Covid_19_s_impact_on_Singapore_.

- Infocomm Media Development Authority, “Annual Survey On Infocomm Usage In Households And By Individuals For 2017,” IMDA – Infocomm Media Development Authority, last modified 2018, https://www.imda.gov.sg/-/media/Imda/Files/Industry-Development/Fact-and-Figures/Infocomm-Survey-Reports/HH2017-Survey.pdf?la=en.

- Smart Nation and Digital Government Office, “Pillars of Smart Nation,” SMDGO, last modified September 15, 2020, https://www.smartnation.gov.sg/why-Smart-Nation/pillars-of-smart-nation.

- Government of Singapore, “LifeSG,” Government of Singapore, last modified August 19, 2020, https://www.life.gov.sg/.

- Cindy Co, “Low Community Prevalence of COVID-19, 0.03% of People with Acute Respiratory Infection Test Positive: Gan Kim Yong,” CNA, last modified September 4, 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/covid-19-singapore-low-community-prevalence-testing-13083194.

- Early Childhood Development Agency. “Annex C: Anchor Operator and Partner Operator Schemes.” Media Room. Ministry of Social and Family Development , 2020. https://www.msf.gov.sg/media-room/Documents/Annex%20C%20-%20Anchor%20Operator%20and%20Partner%20Operator%20Schemes.pdf.

- Early Childhood Development Agency, “KidSTART,” ECDA, last modified March 20, 2020, https://www.ecda.gov.sg/Parents/Pages/KidSTART.aspx.

- “The Big Read: Educators Flag Absentee Rate of Children of Low-income Families As a Concern,” TODAYonline, last modified December 22, 2015, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/big-read-educators-flag-absentee-rate-children-low-income-families-concern.

- Ministry of Manpower, “Summary Table: Income,” Explore Statistics and Publications, last modified September 15, 2020, https://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Income-Summary-Table.aspx.

- Early Childhood Development Agency, “Infant and Child Care Subsidy Calculator,” Go.gov.sg, accessed October 9, 2020, https://go.gov.sg/subsidycalculator.

- Cindy Co, “Low Community Prevalence of COVID-19, 0.03% of People with Acute Respiratory Infection Test Positive: Gan Kim Yong,” CNA, last modified September 4, 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/covid-19-singapore-low-community-prevalence-testing-13083194.

Image Credit: Dollars and Sense

Dollars and Sense

Dollars and Sense

Nikkei Asia

Nikkei Asia

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!