(Equal Justice and Human Rights) The SAP Narrative: Cultural Promotion or Racial Segregation?

By Claire Phua (’22), Bas Jacobs (Exchange), Manar El Amrani (Exchange), and Diore Liu (’23)

As a highly multiracial society, the Singapore government has continuously promoted the importance of multiculturalism. In the words of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, “There is nothing natural about where we are – multiracial, multi-religious, tolerant and progressive. We made it happen, and we have got to protect it, nurture it, preserve it and never break it,” This unnatural multiculturalism would refer to policies such as the ethnic quotas for Housing Development Board (HDB) neighborhoods, where 80% of the population live in, which aims to promote inter-racial interaction through daily interactions. It is against this narrative of enforced and careful integration that the obvious racial segregation that the Special Assistance Plan (SAP) perpetuates stands in stark contrast with. This op-ed seeks to unearth more insights about the SAP, explore its implications on Singapore’s multiculturalism, and offers a way forward through a pluralistic vision of culture-driven education.

Understanding the SAP

The Special Assistance Plan includes the creation and funding of public education institutions in Singapore that are committed to developing excellent bilingual students, specifically in the two languages Mandarin and English. Although also often touted as a way to preserve traditional (Chinese) cultures within Singapore’s cosmopolitan city, the SAP was actually founded in 1979 to promote better English standards in Chinese-medium schools during a time when Singapore’s education was split into English-medium schools and non-English-medium schools. It was established in addition to an Assistance Plan enacted earlier, in January 1978, which sent English teachers to Chinese-medium schools to help improve English standards.

When it first started, only the top 8% of scorers in the Primary School Leaving Exam (PSLE) were sent option letters to join the first 9 SAP schools. These schools were selected based on their foundies ties with the Chinese community, excellent academic performance, facilities, staff and popularity with parents. These SAP schools were then provided with the best teaching staff as well as government assistance to improve their facilities. These plans were a bid to increase the attractiveness of Chinese-medium schools, amidst more parents sending their children to English-medium schools, to preserve the Chinese school environment where “social discipline and cultural values” can be nurtured. This rationale was in line with Lee Kuan Yew’s promotion of the bilingual policy in 1966, requiring all Singaporeans to learn both English and their mother tongue so as to provide a common working language whilst allowing citizens to remain connected to their cultural heritage.

It is interesting to note here that the mother tongue that MOE adopted for Chinese citizens is Mandarin Chinese, this despite the fact that hardly any of the Chinese Singaporeans hailed from provinces that spoke Mandarin Chinese. Afterall, Singaporean Chinese largely hailed from Southern Chinese provinces that speak Chinese dialects such as Hokkien and Cantonese which are largely not mutually intelligible. This brings into question even the proclaimed intention behind promoting ties with cultural tradition if the language Chinese students learn is not even the vernacular of their cultural origin. What was timely with the implementation of SAP and the push to promote Mandarin was the opening of the Chinese economy with the free-market reforms in 1979, where Mandarin was mainland China’s standardised language already widely spoken in Northern China.

Although the intention of these plans were initially two-fold, improving English and retaining Chinese traditions and cultures, the focus shifted to the latter with the end of Chinese vernacular schools in the 1980s when the Ministry of Education announced that all pupils in Singapore would be taught English as a first language and their mother tongues as second languages. Hence, the narrative often heard today focuses on the need to improve our second language and promote traditional Chinese culture. The importance of mastering Chinese is emphasised by the prioritisation of students who do well in the Chinese subject in PSLE. Specifically, students who take and pass “Higher Chinese” are given bonus points for entry into SAP schools,

Today, there are 15 primary SAP schools and 11 secondary SAP schools, which receive additional funding for special cultural and language curriculums and programmes. For example, in response to the strengthening Chinese economy, the Bicultural Studies Programme (BSP) was started in 2005 to nurture the best bilingual students into professionals who could effectively engage China as well as the Western countries. A Review Taskforce in 2007 also led to the development of flagship programmes in SAP schools such as Media Studies in Chinese and Chinese internet broadcasting, filmmaking and drama. On average, SAP students get $300 more per year in government funding as compared to other non-SAP school students.

Implications of the SAP

As the Singaporean language policy assigns mother tongue languages based on one’s ethnicity, students are not allowed to choose or transfer languages under normal circumstances (exceptions include mixed-race children). Crucially, Chinese is the only mother tongue that is offered in SAP schools, and consequently the segregation of students by language essentially becomes a segregation by race and ethnicity, as evidenced by the largely racially homogeneous demographic of SAP schools.

In a conference about diversity in 2016, the SAP came under fire for promoting racial segregation and promoting Chinese elitism. In response to suggestions to allow SAP schools to offer Malay and Tamil to allow a more racially diverse student population, then Minister of State for Education Janil Puthucheary defended the SAP, bringing up the hypothetical situation of a SAP school offering Malay which would allow a handful of Malay students to attend the school, and questions the benefits of doing so:

“Are we saying that this is a good thing because all the rest of the kids now have some exposure to a Malay student or more Malay students in schools?”

The perpetuation of racial segregation by SAP schools has led to concerns that a lack of awareness about racial-plurality has been allowed foster in these Chinese enclaves due to a lack of peer-to-peer interactions to understand other cultures. This was reflected by an SAP alumni, Shaf, who is an Indian Muslim, in an interview with RICE media, that although not all of the students are like this, “some of them really don’t seem to know anything at all about non-Chinese Culture.” She was told things like, “I can’t differentiate between Malay and Indian”, and recalled being asked, “how are you Indian if you’re Muslim” and “if water was halal”. It is also hard to deny the pressures that a student from a minority race would feel representing her entire race and culture in the face of a cohort of students from the majority race.

While SAP schools mandate celebrations of cultural festivals to mitigate the lack of ethnic diversity amongst students – for instance CHIJ St Nicholas Girls’ School holds Bollywood dance competitions to commemorate Deepavali – the time spent on such programmes is scant. Furthermore, such manifestations of “cultural exchange” risk cultural appropriation. If exposure to these traditions are thought of as activities and not as a journey to learn about the culture of others, these attempts at cultural integration are a poor substitute for meaningful social interactions between students of different races.

This was echoed by Zhong Xuan, an alumni of Hwa Chong Institution, who shared with us about the subtle feelings of discomfort that being in a predominantly Chinese environment for a decade led him to feel when he was placed in a wing in National Service that was more racially diverse than his experience in school. “It was not a very bad or very strong feeling, it was something very subtle,” but the presence of such a discomfort led him to question why it exists and where it comes from, as he recognised that it was uncalled for. “While I was lucky in NS to be in a wing that was quite diverse… what’s scary is that most can live a huge chunk of life without confronting this”. Zhong Xuan illustrates that the SAP environment creates a space of comfort for the majority race to be themselves without having to be aware about other races, which does not prepare the students well for interacting with other races outside of these educational institutions. Moreover, past these formal educational institutions – in university or at work – it is much easier for one to choose their circles and continue to avoid interactions with other races.

Segregation at these formal educational institutions — in university or at work — matters because it is much easier for one to choose their circles and continue to avoid interactions with other races. A study co-authored by a postdoctoral fellow at NUS, Elvin Ong, found that alumni from SAP schools do have less ethnically diverse social networks than their peers from comparable but integrated schools, even years after graduation. This hints to the lasting effects of educational segregation on the social interactions of students throughout their lives.

While the above illustrates the negative effects of racial segregation in education, Minister Puthucheary makes an important point when he said that “we do not want to make use of racial tokenism in order to provoke a cultural position.” We should still caution against expressly saying that the SAP should be abolished so that the chinese majority gets more exposure to racial minorities as this presents the latter as objects used in the education system to ensure the holistic development of the majority. While ensuring space and opportunities for inter-racial interaction is important, what provides a strong cause for changing the SAP is the unequal access to educational institutions and opportunities.

“And then what? … Do those kids get a better education because they are learning Malay in a SAP school?

Many SAP schools today are independent schools which receive large donations, possess more resources, and attract students of higher socio-economic classes due to their higher school fees and their accomplished alumni. Topping that off with the additional resources and opportunities that the SAP itself provides, it is true that the league of SAP schools are some of the most popular elite educational institutions in Singapore. The segregation by language thus denies minority races the opportunity to attend these institutions.

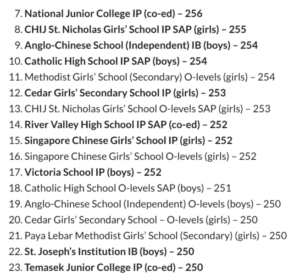

While one might argue that minorities have access to other schools that provide similar opportunities as SAP schools, under certain circumstances, race as an explicit qualifier may compound with other factors such as residential geography to increase the overall barrier to education opportunities. Let us take the plausible case of a male minority student who lives in Boon Lay, in the west of Singapore, and scored 253 for PSLE.

Source: https://www.salary.sg/2019/top-secondary-schools-2019-cut-off/

Taking a look at this list of secondary schools based on PSLE cut-off scores from 2019, this student might have to opt out of the opportunity to have an Integrated Programme (IP) education as the three IP schools he qualifies for are either SAP schools (i.e. River Valley High School which is located in Boon Lay), or located in the east close to an hour and a half away by public transport (Victoria School, Temasek Junior College). Essentially, the SAP can increase the burden of residential geography on some minority students by increasing the travel time demanded of them to access education opportunities. It is these unfair experiences minority students experience from arbitrary barriers for entry that we should, as a multi-racial society, strive to equalise and alleviate.

What Next for the SAP?

The topic remains in heavy debate. In February 2019 Education Minister Ong Ye Kung reasserted the relevance of the SAP schools in an interview with The Straits Times, saying that “countries around us are catching up or surpassing us in teaching their people multiple languages” and that “we should preserve our programmes and institutions to develop biliterate and bicultural talent at this crucial point in history.” However, this official emphasis on the pragmatism of the SAP programme seems to fall short in addressing the SAP’s explicit emphasis on the Chinese language and culture, at the exclusion of other cultures like Malay and Tamil culture. However, we can try to understand this bias if we turn to Lee Kuan Yew’s promotion of Confucian values, or “Asian values”, during Singapore’s developing years.

“Singapore depends on the strength and influence of the family to keep society orderly and maintain a culture of thrift, hard work, filial piety, and respect for elders and for scholarship and for learning,” Lee wrote in “From Third World to First. “These values make for a productive people and help economic growth,” he added. The choice to emphasise Chinese culture, at a time when Westernisation was affecting the country on a whole, may have been a result of Lee placing certain Confucian values at the root of his construction of Singapore, values which he felt were important to promote to safeguard the work ethic of Singaporean society.

Especially given that Minister Ong recently endorsed that “we should review the programmes with a view to enhancing and improving them, across all our mother tongues”, it begs the question: are the purposes of the SAP programme still relevant today? If it is about the pragmatism of promoting bilingualism and biculturalism in an increasingly multi-lingual world, why favour one language and culture over the rest? Minister Ong’s point about the fear of undoing programmes and institutions that have been working well to promote bilingualism is important, then perhaps we should strive to update and improve our systems to promote multilingual and multiracial education for all.

We need to first acknowledge that Chinese language-only restrictions for SAP schools are in themselves barriers to good educational opportunities for non-Chinese students, which should be lowered. Furthermore, all students, regardless of race, should have access to the additional funds allocated to SAP schools for enhanced cultural immersion. SAP schools should thus offer other mother tongue languages, and simultaneously diversify cultural programmes to draw on the values and intellectual traditions of Malay and Tamil cultures in equal proportion. To give a couple of examples, SAP schools can introduce classes on Singaporean Malay poems which “embody the aesthetic as well as the cultural and political values of Malay society”, or organize visits to the Indian Heritage Centre to understand the diverse history and traditions of the Singaporean Indian community. Looking to our immediate regional backdrop, classes covering Islam Nusantara’s values of being moderate, tolerant, balanced and inclusive, align well with Singapore’s proclaimed social model of pluralism and multiracial harmony, while Javanese culture emphasizes the life philosophies of politeness, thoughtfulness, and humility, amongst many other values.

Fundamentally, we need to shift the narrative of “Asian values” to be more inclusive and to actually reflect the diversity of cultures in Asia. Indeed, the moral values that SAP seeks to teach through its cultural programming should still stand even when abstracted from the Chinese cultural context, so we should find solutions for a more culturally inclusive moral and value education. As Zhong Xuan reflects, “Do you really need to teach life lessons as a Chinese thing?” While the life lessons he learnt were valid, labelling it as Chinese culture necessarily excludes others and “what’s the point of building a strong culture if it is built around exclusion”? Only through reducing arbitrary barriers of race and allowing equal access can we really take a step towards calling ourselves a multiracial and culturally plural society.

Image Credit: Dunman High School website

Article Revision Notice: The concluding 2 paragraphs of this article were revised in response to community critiques. The full editorial note can be found on our Facebook page dated July 2020.

https://dunmanhigh.moe.edu.sg/

https://dunmanhigh.moe.edu.sg/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!